During these past two weeks, I have been working with primary sources such as the College News, President Park’s papers. Initially, I looked through every mention of the word “Chinese” in the College News from 1915 to 1937, then at mentions of the word “Oriental.” Particularly in the early years of this time period, there was much discussion of missionary work in China. Missionaries working in China would speak at chapel, and articles would discuss recruiting efforts for teaching positions in China, and Chinese students and the nation as a whole appeared to have many advocates at Bryn Mawr who would appeal for aid on their behalf. These connections persisted over time: One article, “Peace Council Aids Chinese Students,” discusses how relief money was sent to Liu Fung Kei (1922), a former recipient of the Chinese Scholarship who had become the head of a middle school in southern China.

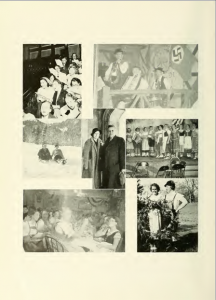

Looking through President Park’s papers and the Chinese Scholarship Committee records gave me a sense that administrators were very invested in the welfare of the students, who often thrived at the college and kept in touch after graduation. One holder of the Chinese Scholarship, Vung-Yuin Ting, won an award for being the highest ranked student of her class in junior year. Later records in President Park’s papers show people at Bryn Mawr sending her money while she coped with the disorder of war-torn China. The newspapers and yearbooks show that the Scholarship recipients were very integrated into college life and participated in a range of extracurricular clubs and activities. Students showcased their culture through traditional dance and musical performances. One article about Ting mentions how she learned a lot about China because Americans expected her to knowledgeably explain everything related to China, including about regions far away from her hometown of Shanghai. It goes on to say, “She was also expected to understand the foreign and domestic policies of her government so that she could explain them to ignorant Americans…Churches and schools in and around Philadelphia requested her to lecture on Oriental education, government, or geography.”

Articles about China reveal a mixture of admiration, fascination with, othering of, and disdain for Chinese culture. Many events were hosted and speakers invited to discuss Chinese art or philosophy. Though one article praised the long history of dedication to education in China, it also suggested that China would eventually need to switch to a romanized writing system to progress. In an early 20th century yearbook entry, a student describes how she and her friends created “grotesque” costumes for a play to represent Chinese and Japanese, then good-naturedly noted that a Japanese student had told her how inaccurate the costumes were. While the student clearly saw Chinese and Japanese culture as strange and perhaps inferior, this sense of otherness did not result in any hostility or distaste toward the Japanese student.

One area that I have struggled with is learning about the experience of Chinese-American students, who are comparatively invisible. Articles giving freshman class demographic statistics mention country of origin, but not race. I would like to locate the names of the first or early Chinese-Americans on campus. My hypothesis is that Chinese-Americans would have found it much more difficult to fit in and would not have been as well treated as the foreign-born students. They would have been less likely to belong to elite social classes, a background foreign-born Chinese shared with most students at Bryn Mawr in the early 20th century. Additionally, foreign-born Chinese were models of success for the civilizing mission who were expected to return to China and contribute to its Westernization. By contrast, Chinese-Americans would likely be perceived more as a “race problem.”

I have located a Chinese-American graduate student, Grace Lee Boggs, who received a doctorate in philosophy from Bryn Mawr in 1940 and went on to become an important civil rights activist in the 60s. However, though her autobiography, Living for Change, does discuss the discrimination she faced as a Chinese-American, it touches only very briefly upon her time at Bryn Mawr. Mentions of Chinese-American identity do not appear in the College News until the 80s and 90s.