In starting to research the history of fantasy narratives on Bryn Mawr’s campus, I was really interested in the ways that the paratextual information surrounding certain objects in Special Collections differed from the norm of the institution. Most material held by Special Collections comes from the families of important members of the community, donated after the individual had found success in their life—and almost always had passed away—before acquisition of their materials. This is really evident in the structure of the archive, with collections almost exclusively being named after specific individuals, rather than the sweepingly broad collections of the Friends Historical Library who have collections organized by topic.

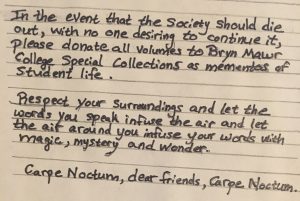

The material I’m looking at for this project is different in a really interesting way; in several documents I’ve come across, students mention wanting to donate the material to Special Collections once it ceases to be used, to install their relatively secret endeavors in institutional history. While there might have been some latent shame and embarrassment in maintaining a fantasy roleplay journal with seven of your closest friends, there was still a very real drive to have others witness their experiences and share in the joy that these journals gave them. The end result is collections of journals, photos, and backsmoker diaries that don’t have any one distinctly important author or subject, any singular Katherine Hepburn, Emily Balch, or Marianne Moore. Instead, the emphasis is on the collective, and in a sense the subject is what these people got to experience together, with faces and names fading in and out as students matriculated and graduated.

While these sentiments of hope to preserve via institutional history might have arisen from the authority and public presence on campus of the college archives in the late 20th century (which did not exist in nearly the same capacity before, which mainly the administrations’ papers were held rather than students’ papers), I still saw similarities to more traditional collections that are held in Special Collections, where members of the class of 1914 talked of how they expected their children and grandchildren to one day read through their diaries and class notes, and even figures in the administration over the course of the college’s history were concerned about how their words might look in the vacuum of history, outside of the moment that they were written.

The fact of the matter is, we all want to be remembered. We all want to be a part of something bigger than ourselves, whether that takes place in the form of a campy and fantastical LARP with your friends, the preservation of your name in a book on the shelf in an archive, or—as is the case here—both.

-Beck Morawski ’21