the Chinese Scholarship at Bryn Mawr and the Chinese-American Journey

Chapter 1

Children’s hoop toys and gramophones, beds, chairs, pots and pails, large wood-paneled ice boxes — or refrigerators, as they were still called in 1900 San Francisco. The detritus of upturned lives lay exposed throughout Chinatown: beside cable car-less tramways; near the hotel basement where they had found a middle-aged Chinese man dead; visible from the doorway of the coffin shop where an autopsy had revealed the telltale swollen lymph glands of the Black Death. Just three days after the discovery, health inspectors had gone door to door whitewashing the basements of all but the “wealthy and unusually clean Chinese” and airing out household goods on the streets, determined to eradicate what they believed, as one publication stated, to be “an Oriental disease, peculiar to rice-eaters.” Ubiquitous leaflets announced a 10-cent bounty for every dead rat, recommending the cage trap for best outcomes. While San Francisco mobilized to control the rat population and contain the plague, government officials and doctors also spread fear against another perceived carrier of disease: Chinese residents. Police officers wielding pistols and nightsticks enforced a swiftly imposed quarantine. Hospital officials were permitted to “forbid the sale or donation of transportation by common carrier to Asiatics or other races particularly liable to the disease.” By the time the bubonic plague epidemic ended in 1904, authorities had floated such drastic measures as razing Chinatown and forcibly relocating thousands of Chinese people to a detainment camp on Angel Island.

By 1900, the idea that “Mongolians” were uniquely susceptible to disease had already entrenched itself in San Francisco, where morally degenerate Chinese prostitutes were believed to be infected with a special, nearly untreatable strain of syphilis. In 1916, President M. Carey Thomas’s address to Bryn Mawr’s incoming first-year class mirrored the rhetoric of the San Franciscan government officials, tying undesirable racial groups to disease:

“The United States is fast becoming, if it has not already become, the melting pot of nations…The diseases of European poverty and filth are brought here by our foreign immigrants, and like our present epidemic of infantile paralysis are propagated under conditions we cannot control.”

Professor Lucy Donnelly

That same year, Bryn Mawr College set up the Chinese Scholarship to award full tuition to women from China, spearheaded by English professor and Bryn Mawr alumnus Lucy Donnelly, who had been inspired by her sabbatical travels. The Scholarship students were among the first nonwhite attendees of the college.

Thomas’s speech may have articulated white supremacist views, but it also ascribed to China “an unchanging tradition of inconceivably difficult and preposterous learning [that] has kept an extraordinarily intellectually gifted people shackled and stationary,” suggesting that with exposure to the right, Western education, China could match the U.S. Chinese-Americans in the early 20th century retained their reputation as inherently unassimilable and un-American hordes. Yet the first hints of the model minority status they would acquire within a few decades were beginning to emerge, as universities such as Bryn Mawr welcomed Chinese international students.

Chapter 2

Students protest during the May Fourth movement.

The sea of chanting, flag-waving, placard-carrying students were fed up. They protested the loss of Germany’s possessions in Shandong province at the Versailles Peace Conference, which had been humiliatingly ceded to Japan despite China’s participation on the winning side of the war. President Woodrow Wilson, a former professor at Bryn Mawr, had issued his 14 Points calling for national self-determination. Young Chinese tired of wangguo, or national defeat, at the hands of imperialists took notice of both Western hypocrisy and their own government’s fecklessness. In the wake of the nationwide May 4, 1919 student protests, China radicalized. The anti-Confucian New Culture Movement, the Anti-Christian movement, Marxism, anarchism, and more collided with one another like water molecules nearing boiling point. Within the past decade, an imperial dynasty had been overthrown, democracy had been won and then lost and then tenuously re-established, and the success of the current regime hung by a thread. China in the early 20th century was a volatile new nation undergoing growing pains, and American missionaries readily jumped into the ideological fray.

Bryn Mawr students heard about the 1919 uprisings at Sunday chapel. President Mrs. Lawrence Thurston of Ginling College, a women’s college in China, discussed the student strike there “to prove that Chinese women are taking their places in politics,” as an article from the College News, the college newspaper and precursor to the Bi-College News, reported.

Women at Bryn Mawr too were taking their places: On December 5, 1916, alumna and National Woman’s Party activist Mary Gertrude Fendall unfurled a yellow banner reading “Mr. President: What Will you do for Woman Suffrage?” during Wilson’s speech at BMC. Five years later, with Wilson still in office, the 19th Amendment was ratified, giving women the right to vote. The Prohibition, a testament to the political potential of female Protestant moral crusaders, was on the horizon. And the women’s foreign missionary movement was the largest women’s movement in the country. College-educated American women, still a small and exceptionally privileged group (Bryn Mawr students were by and large the daughters of college professors, lawyers, bankers, manufacturers, and physicians), pushed frontiers domestically, and were eager to try their luck abroad.

***

M argaret Bailey Speer, a member of the class of 1922, was the daughter of a prominent Presbyterian missionary. She looked up to her mother, who had also gone to Bryn Mawr but never graduated, and whom she credited with instilling an early commitment to feminism. As a student, she served as president of the Christian Association. “[President Thomas] asked me what I intended to do when I was through college and I told her some sort of work with the women in the East,” she wrote. “She seemed to think that was very nice and talked very amiably about the working girls she’d seen in China and Japan.” Speer left the U.S. three years after graduation to teach English at a women’s college in China called Yenching University, where she later became dean.

Speer was one of many: Students at women’s colleges such as Bryn Mawr comprised a major portion of the influx of American missionaries in China. One 1917 article in the College News was headlined, “China has Golden Opportunities: Teaching positions practically unlimited.” The article continued, “Practically all such positions open to college women are under mission boards and in mission schools.” The schools could count on a rising demand for girl’s and women’s education in China. Suffragists had broken into parliament to protest the exclusion of women’s suffrage from the 1912 constitution. Social Darwinist ideas about racial competition and fitness had also made their way to China, leading some Chinese to support women’s education as a path to national glory.

Driven yet playful, Speer enjoyed the excitement and novelty of Beijing. It was a far cry from the tranquility of life at Bryn Mawr, or at Sweet Briar in Virginia, where she held her first teaching position. Speer, with her exuberant personality, could not help but chafe against and disdain the traditionalism of some of the older Chinese gentlemen. As she settled into her new surroundings, she indulged in her sense of fun, going to costume parties dressed as a man, or staying out all night and returning home in the morning dressed in evening clothes. Like many young missionary women, she bobbed her hair, at the time a daring style that carried rebellious flapper connotations. Another missionary teacher at the Shanghai Christian Medical College for Women wrote to her parents about her new haircut: “It is so much more convenient, cleaner, and more comfortable. At present there are more women in Shanghai with bobbed hair than with long hair.”

An undercurrent of normalized anxiety characterized the atmosphere at Yenching, which was not insulated from domestic political instability or from tensions between China and Japan. In 1926, a Yenching student died by bayonet during a student demonstration. For Speer, going about routines such as grading papers while the threat of war loomed was like being “perched on top of a volcano.”

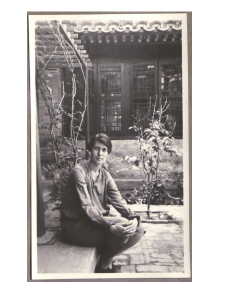

Portrait of Margaret Bailey Speer seated on a stoop at Yenching University.

An ingrained sense of white superiority flavored the mission schools’ stance on their role in building a new China. Yenching University president John Leighton Stuart wrote that “the Christian movement will save not only individual Chinese, but China…as go the students, China will follow with all its vast population.” Speer, however, grew conflicted about the paternalistic dynamic between missionaries and the native population, a tangled problem that preoccupied her throughout her life. She was initially reluctant to take up the dean’s position, worrying that Yenching should instead appoint a Chinese dean. At the same time, Speer focused on foreignness rather than racial difference as the source of the condescension.

The “civilizing mission” missionary ethos significantly influenced Bryn Mawr College policy with respect to Chinese women. In 1919, President Thomas, a cosmopolitan who lit her Deanery garden with Japanese lanterns, was selected by the Federated Women’s Council of Foreign Missionary Societies to visit missions in China. Earlier that year, she went on a trip around the world and visited girls’ schools, particularly mission schools, to consider scholarships for the “cleverest” students to study at U.S. women’s colleges. A College News article noted, “She thinks this is the most practical way of helping Oriental women to help themselves.” In the vein of John Leighton Stuart and other philanthropists of the era, Thomas aimed her humanitarian impulses toward cultivating exceptional leaders to achieve racial or national uplift.

***

Another member of the Class of 1922, Chinese Scholarship recipient Fung Kei Liu (‘22), followed a path similar to Speer’s, starting her own school for girls in China. Like Speer, she was participating in a family legacy. Her older sister, a graduate of Wellesley and Columbia, ran a mission girls’ school in Canton. In a revolving door pattern, the mission schools were feeders for the Chinese Scholarship, and Bryn Mawr in turn provided a supply of mission school teachers.

Fung Kei Liu’s journey was a model case for the outcomes both mission schools and Bryn Mawr College hoped for from their endeavors. Foreign-born Chinese students would bring Western attitudes and knowledge home to modernize their country, essentially performing as brand ambassadors for the American way of life. A Chinese Scholarship Committee brochure updating readers on the recipients’ lives complimented Vaung-Tsien Bang (‘30) by saying, “She unfailingly wins friends for China, and we feel certain when she returns, will win friends for America.”

Brochures and letters from administrators effusively praised the scholarship holders, leaving few traces of them outside of the mold of accomplished students concerned and articulate about China’s political situation. Letters to the Committee from students overflowed with gratitude and contained promises to fulfill the Committee’s expectations. One student wrote, “Considering the great changes going on in China, I am sure what I can learn here will be very valuable both to my own career and to the country.”

Chinese students played the role of guests shown around the United States with the utmost hospitality so that they would be effective paragons of Americanization for their country. The specific linking of Chinese identity to foreignness benefited the students, especially on the East Coast, even as it ostracized Chinese-Americans. The students’ willingness to assimilate endeared them to their hosts, for whom they represented living proof of (white) American cultural supremacy. They were treated well, but implicitly only so long as they did not overstay their welcome — or, for a eugenicist like Thomas, stay long enough to contribute their genes to the American melting pot.

Chapter 3

In nearly every respect, the pale, impeccably suited man with a large, distinctive mustache seemed to be an upstanding American citizen. After spending his childhood in San Francisco, he attended the University of California, Berkeley before moving to Hawaii to start a family. He went to a Protestant church on Sundays and ran a successful business. However, Takao Ozawa was not an American citizen, and in 1922 he knew that he could never become one. As a Japanese man, he was considered ineligible for naturalization, a path available under federal law only to an alien who was a “free white” or of “African nativity and descent.”

After being denied citizenship in 1916 after 20 years of living in the U.S., Ozawa had taken his case to the Supreme Court, arguing that he qualified as a “free white.” After all, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 only specifically barred Chinese from naturalizing. In his own brief, Ozawa highlighted his good character and assimilation to American culture. He also claimed, “In the typical Japanese city of Kyoto, those not exposed to the heat of summer are particularly white-skinned. They are whiter than the average Italian, Spaniard or Portuguese.”

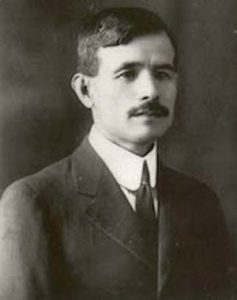

Takao Ozawa

Despite his eventual loss, Ozawa had reason at the time to believe his case would succeed. George Dow, a Syrian immigrant, had taken his citizenship case before the United States Court of Appeals, Fourth Circuit in 1916, claiming to be white, and had won. Moreover, even in California, where race laws directed at the substantial Asian population were most stringent — anti-miscegenation law in California, unlike most states, mentioned “Mongolians” — Japanese people occasionally succeeded in separating themselves from other minority groups. In 1906, an intervention from the Japanese government persuaded President Theodore Roosevelt to force California to allow Japanese-American students to attend white public schools rather than the Oriental Public School for Chinese and Koreans.

Ozawa’s case is just one example of the fluidity of racial identity, particularly for those falling outside the black-white binary. The term “Asian-American” would not be coined until 1968, and Asian racial status was constantly contested and highly contingent upon local conditions. For example, in Washington, DC, all Chinese attended public schools meant for white children in part to show respect toward the many Chinese diplomats’ children.

Ozawa could also count on his membership in the upper middle class. Just as the Chinese Exclusion Act only barred Chinese laborers from entry to the U.S., exempting merchants and scholars, upper-class Chinese were frequently exempted from negative racial stereotypes surrounding Chinese-Americans, as in the case of the “wealthy and unusually clean Chinese” in plague-ridden San Francisco.

Ozawa’s story, like the Chinese Scholarship, highlights the limited efficacy of acting out the model minority type as a means of attaining equality and respect. He checked every respectability box available, but he was never accepted as American.

***

Vung-Yuin Ting holding a hoop during a May Day celebration.

The Chinese Scholarship recipients by and large came from privileged backgrounds that matched the social composition of the larger student body, and many had finished high school in the U.S. These factors helped them integrate, though fewer than a handful of Asian students coexisted on campus at any given year during the interwar period. Little evidence of any struggles they experienced at Bryn Mawr, other than the occasional mention of “shyness,” exists in archival records, written through the eyes of the administrators who discussed them with potential Scholarship donors. To the pride and delight of their sponsors, they participated in extracurriculars, performed Chinese dance and musical pieces at showcases, and excelled academically. One holder of the Chinese Scholarship, Virginia Dzung (‘43), was elected editor of The Lantern. Another, Vung-Yuin Ting (‘35), won an award for being the highest ranked student of her class in junior year.

Ting, like Fung Kei Liu, was a model student. She was diligent, poised, efficient, and highly conscious of the lack of cultural understanding between Chinese and Americans. At Bryn Mawr, she had no patience for the Diction or Hygiene required classes, and liked a “short, snappy” school year so that she could spend her summers catching up on reading. She took seriously the burden of representing China to Americans, even studying up on regions far from her hometown to equip herself to answer questions about them. Despite her youth, she became a local expert on China affairs, lecturing frequently at churches and schools in the Philadelphia area.

Ting had her work cut out for her, both because of Americans’ thirst for information about China, and because of their ignorance. In a 1904 yearbook entry, a student describes a first-year performance based on a Japanese play, given to the senior class. The student and her friends created costumes to represent Chinese and Japanese, then good-naturedly admitted that a Japanese student had commented on their inaccuracy. While the student clearly saw Chinese and Japanese culture as strange and perhaps inferior, she also felt drawn to it, and her sense of otherness did not engender distaste toward the Japanese student. By the early 1930s, during President Marion Park’s tenure, the Bryn Mawr community had many more opportunities to interact with Chinese people and culture, but similar attitudes persisted.

1904 yearbook entry.

These mixed racial views contrasted with the outright hostility that other minority groups confronted. Bryn Mawr forced Enid Cook (‘31), its first African-American graduate, to live off campus, and only admitted her after lengthy board discussions about whether African-Americans should be allowed to attend at all. The College’s first president, James Rhoads, was involved in Quaker groups educating Native Americans and the formerly enslaved, and the college itself provided classes for its predominantly African-American staff of maids and porters. But they were given the menial training designed for life within an economic underclass, or forced to undergo often-traumatic cultural reprogramming. The Chinese Scholarship students were granted a full academically rigorous curriculum and treated as intellectual equals.

While Sunday chapel speakers at Bryn Mawr called for America to assist China because, as one speaker claimed, Confucianism’s emphasis on filial piety prepared Chinese for Christianity, Muslims were demonized. One speaker portrayed Islam as a threat, arguing that Islam was the source of “illiteracy, child marriage, and other social evils” in the Middle East.

And Bryn Mawr’s Sunday chapel speakers, such as Mrs. Thurston of Ginling College or Mrs. Edward Howe of Canton Christian School, spoke frequently about China. During her talk, Howe reminisced about meeting Fung Kei Liu when she was just a “little girl with pigtails,” then again at Bryn Mawr, where she had “bobbed her hair and assimilated many American mannerisms.” For Howe, Liu’s adoption of an avant-garde style like the bob demonstrated her Americanness, even though many missionaries picked it up from Chinese women, because Howe could not conceive of a model of modernity outside of Westerndom. Many at Bryn Mawr found Chinese culture interesting and even admirable, but only as an artifact of history, not as something to be preserved. It was an indication of foreign Chinese individuals’ exceptional receptiveness to assimilation, which allowed them the access to white-dominated spaces that later helped generate a model minority reputation for Chinese-Americans.

Chapter 4

“And if a stranger sojourn with thee in your land, ye shall not vex him.” (Leviticus 19:33, KJV)

“For we are strangers before thee, and sojourners, as were all our fathers: our days on the earth are as a shadow, and there is none abiding.” (1 Chronicles 29:15, KJV)

Upon graduating from Barnard College in the late 1930s, Grace Chin Lee was clueless about what she was going to do. As a Chinese-American woman with a degree in philosophy, her applications to secretarial or salesperson roles would likely be met with a frank “We don’t hire Orientals,” especially in the job-scarce environment of the Depression era. Meanwhile, a civil war raged in China. Bryn Mawr offered a Chinese graduate scholarship to ease travel to the U.S. Lee applied, interviewed, and was accepted.

Lee was born in 1916 in Providence, Rhode Island. Her father, who had immigrated from a peasant village to the U.S. in the early 1900s, chose to name her after the church member who taught him English. In her autobiography, Living for Change, she wrote, “In those days it was assumed that the Chinese in this country were only ‘sojourners,’ that we/they would be going back home after making and saving enough money. In fact, as a child I thought goingback was one word.”

Lee’s entrepreneurial father aggressively sought upward mobility. He built a Chinese restaurant chain that became a household name and drummed his faith in education into his children, eventually giving Lee the opportunity to earn a doctorate.

Lee found in Bryn Mawr a picturesque scholarly haven, with its broad expanses of grass, Jacobean Gothic buildings, and luxurious dorms catering to the habits of the wealthy scion that made up its undergraduate population. The sumptuousness felt foreign and noteworthy to Lee and her fellow graduate students, who tended to be “as poor as church mice.” She observed, “Black maids, dressed in gray uniforms with white collars, made our beds, cleaned our rooms, and served us our meals three times a day at tables with fine china, cutlery, and cloth napkins.”

“In those days it was assumed that the Chinese in this country were only ‘sojourners,’ that we/they would be going back home after making and saving enough money. In fact, as a child I thought goingback was one word.”

When Lee left the Bryn Mawr bubble in 1940, she remained a woman with a philosophy degree and poor job prospects, but she had gained a budding determination to “become active.” She ended up in Chicago, found work at a university library, and went door to door looking for someone willing to rent a Chinese person a room. She was denied again and again.

***

Bryn Mawr’s close ties with educated foreign-born Chinese fluent in American culture and decades-long investment in China’s future conditioned it to accept Lee. As China became engulfed in civil war, the Bryn Mawr community stepped in and offered aid, and Lee was only one beneficiary.

The Chinese Scholarship alumni in China, caught up in the political turmoil, kept in touch with administrators about their lives and discussed their new hardships. Fung Kei Liu (‘22) and Vung-Yuin Ting (‘35) both received well wishes and financial assistance, Liu to keep her school running, and Ting to buy safe powdered milk for her baby at wartime prices.

Ting had realized her dream of continuing a family tradition by becoming a doctor and working to heal her country, only to find it shattered by war. In her communications with the College, she described streets reduced to rubble and eerily emptied, as if their inhabitants had abandoned them to the ravages of time. She talked about waiting for death in dark and still dugouts, patients and hospital staff crammed together, and hearing the whine of approaching Japanese planes. In 1940, she nearly died. A bomb had hit her hospital and trapped her under debris, throwing up clouds of dust. Fortunately, she had put up her left arm between her head and the oncoming crush, leaving an air pocket, and survived mostly uninjured. “There could have been so many ‘ifs’, only one of which could change my year of silence into a silence of many years,” she wrote, referring to her year of no contact with Bryn Mawr, and signed her letter, “With love.”

Bryn Mawr responded quickly to the crisis because foreign-born Chinese students had accumulated staunch lifelong allies for their cause at Bryn Mawr and the United States, people with backgrounds like Margaret Speer’s. Speer, like Ting, was caught up in war, ending up stuck at an internment center for enemy aliens in North China. The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941 had pushed her to leave Yenching. She would arrive in the U.S. in 1943 to take up her post as the headmaster of the Shipley School, at the time a girls’ boarding school. She continued her advocacy for China despite being away from it, serving as treasurer of the Chinese Scholarship Committee.

In the late 1960s, a group of Speer’s old Yenching students invited her to meet in Honolulu. The Chinese Exclusion Act had been repealed during World War II; China was a key U.S. ally, so the Act seemed diplomatically embarrassing. But only in 1965, at the height of the Civil Rights Movement, did the Immigration and Nationality Act finally abolish the racially discriminatory immigration quotas that had been in place since 1882. Speer’s students had immigrated to the U.S, became citizens, and built lives as college professors, lawyers, bankers, manufacturers, and physicians — the same demographics that sent their daughters to Bryn Mawr in 1915.

***

Grace Lee Boggs at home.

Grace Chin Lee, later Grace Lee Boggs, ended up sleeping rent-free on a kind Jewish woman’s basement couch, and soon involved herself in a housing activism group called the South Side Tenants Organization, where her interactions with African-American community organizers sparked her dedication to labor and racial justice, years before the still nascent Asian-American movement truly picked up steam. In defiance of the expectations that defined her childhood and the landlords who refused to rent her rooms, Lee had found a home, and she stayed.

She died in her adoptive city of Detroit at a hundred years old, a hundred years after the founding of the Chinese Scholarship. In 2012, at 96, she gave a talk at the University of California, Berkeley, detailing her thoughts on activism. She said: “Radicals don’t usually talk about souls, but I think we have to. What I mean by souls is the capacity to create the world anew, which each of us has.”